ON Collages & COLOR

An interview with Stephen Batchelor and David Batchelor by Ronn Smith, in Tricycle, the Buddhist Review

Stephen Batchelor began making collages from found materials in 1995. Until recently, however, they were seen only by a few family members in Stephen’s home. This changed on May 20, 2023, when a small exhibition of eight collages opened at Galerie 727, in Montmorillon, France. The show, which included both old and recent work, was curated by Keith Donovan, Galerie 727’s director.

I started making collages when I was about twelve years old. I vividly remember the delight in pasting together unrelated pictures cut from magazines and newspapers, then reorganising them to form another picture altogether. There was something magical about reconfiguring random elements into a new whole. Perhaps it was then that I first grasped what creativity meant: to bring into being something that had not existed before. Collage has since become a guiding principle for much of what I do in life. More and more I think of my writing as a kind of collage, the only difference being that my books are collages of words and paragraphs rather than old photographs and torn scraps of paper. The core question and struggle that drives both my collage and written work is the same: how does this go together with that? I may not be able to explain logically why two words or two scraps of coloured paper go together; but I feel it aesthetically.

I have been making collages slowly but steadily from 1995, but until this year I have never shown them in an art gallery. They cover the walls of my home in France, but I’ve had no interest in making them public — nor, until recently, have I been invited to do so. Instead, I think of them as private, non-verbal counterparts to my written work. The collages function as a kind of subconscious process that parallels the conscious act of writing, providing an invisible depth, patterning and colour that runs beneath the surface noise of words.

I do not think of my collages as “Buddhist.” As with art from all cultures, they may reflect certain Buddhist themes and ideas, such as transience and suffering, but they rarely include recognisably Buddhist elements. Yet I cannot deny that these images have emerged from a life steeped in the Dharma. Let’s put it this way: my collage work is a non-verbal medium within which to explore the same existential questions that Buddhism seeks to address verbally. Each collage tackles the wordless question: Why am I here? The “here” is present in every piece of material I find on the streets or in people’s garbage, which I rescue from oblivion and restore to the world so it can be reconfigured and contemplated anew rather than be forgotten and ignored.

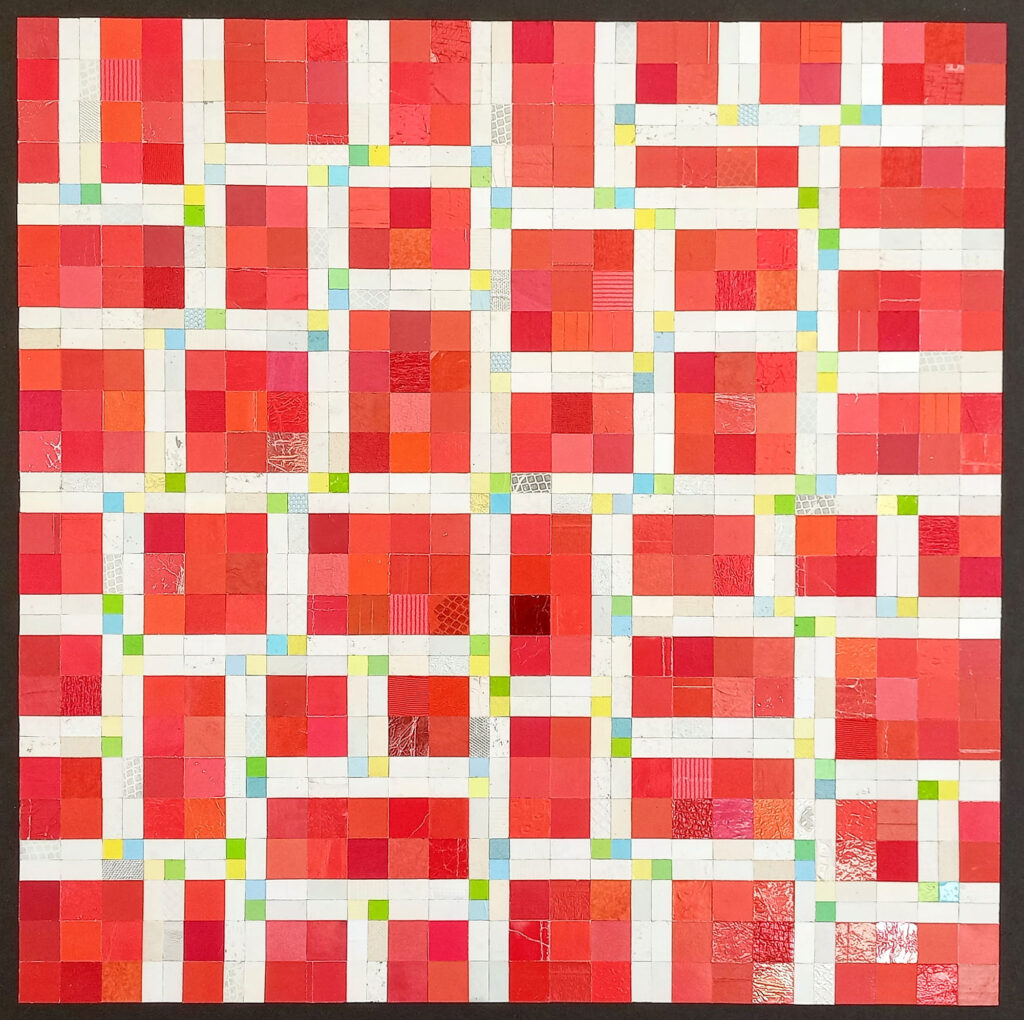

As much as I try to keep Buddhism out of my work, it tends to find its way back in. It is sometimes there in the titles I give to the pieces. The first large scale collage I made is a triptych called Trikaya, which refers to the three “bodies” of the Buddha — the Dharma Body, the Archetypal Body, and the Manifest Body. These Mahayana Buddhist ideas were doubtless always in the background, but what drove the work was the search for enough pieces of discarded paper, cloth and plastic from which to make it and the formal principles that determined how to organise the materials once I had found them. The next sequence of collages was titled Octet, which consisted of four diptychs. Each diptych consists of an abstract collage of four colours (red, blue, white, yellow) side-by-side with a matching collage made from old photographs, texts, printed remnants of cloth etc. Whether in Pali discourses or Tibetan monastic textbooks, red, blue, white and yellow are considered the four primary colours. This fourfoldness finds itself reflected in many classic doctrines: the four tasks, the four truths, the four paths, the four immeasurables and so on. Buddhism is more implicit in Octet, but in some ways more fundamental to the work than in Trikaya.

Both Trikaya and the first diptych of Octet will be shown at the exhibition in the forthcoming exhibition in Montmorillon. In addition, I will include a sequence of four recent works, collectively titled On Black, made during and after the Covid lockdown. These grew out of the Octet series but have taken on a life of their own, in which the Buddhist influence has almost entirely disappeared. Over time, I have learned to trust the internal logic of the collages and abandon my own desires for how they should be. I have no idea what a piece will look like until it is completed. On every occasion I am surprised by what emerges. I find myself elated and disappointed at the same time. But the seed of the next collage always lies buried in that disappointment. The uncertainty and imperfection of the world are what keep me pursuing this path. Without suffering, there can be no beauty.