I was eighteen when I decided to leave England and travel overland to India. It was 1972. After leaving grammar school, I spent the winter working in an asbestos factory, saved every penny, and told my mother I’d be back in a year. She was still hoping I’d become a doctor or an architect. But she didn’t stand in my way.

Apart from my mother and brother David, nothing in particular bound me to England. I felt suffocated by the oppressive class hierarchy of the place had no interest in joining the rat race. I was a child of the 1960’s, a romantic, an idealist driven by a sense of adventure and a longing for freedom — whatever that might be.

It took me six months to get to India. By the time I reached Dharamsala I needed to stop. This old British hill-station in the Himalayas was a Tibetan refugee settlement, home to the Dalai Lama and his government-in-exile. I’d never encountered a culture so exotic, and rich in potential meaning. It filled me with enthusiasm, optimism, and a curiosity I’d not known before.

I was interested in the big questions, like the meaning of life. My teachers at school never brought it up. I would have been surprised if they had. But the impoverished monks I met here seemed to care about nothing else. They had an extraordinary philosophy, fully integrated with a wide array of spiritual practices. On top of all that—although their living conditions as refugees were appalling—they seemed entirely happy and at ease with themselves. This impressed me.

More than anything else, I was moved by the welcome I received. These people wanted to share their knowledge and culture with me, a complete stranger. But I wasn’t interested in just studying their religion; I wanted to be like them. Taking ordination as a monk was the next logical step, but at this point the asbestos money ran out.

Back home my mother was bewildered by my interest in a religion about which she knew nothing. She worried how I would support myself, find a career, earn a pension. But she recalled how her own father had thwarted her ambitions to go to art school. ‘Young ladies don’t do that,’ he’d told her. That had blighted her life and she was not going to repeat the same mistake with her own children.

With her nervous blessing she gave me access to a small inheritance from my grandfather—about £1200, which at the time was a considerable amount. These funds enabled me to return to India, take ordination as a monk and pursue my studies for three more years. I then moved to Switzerland with my teacher Geshe Rabten. After the inheritance money ran out, Geshe found me a sponsor. I didn’t need much. I lived simply.

I spent nearly five years in Switzerland. During this time I learned to speak and read Tibetan. I studied Buddhist logic, epistemology, philosophy, and psychology. I translated Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life into English. I debated and argued with my fellow monks for hours, struggling to grasp the meaning of key Buddhist doctrines and concepts.

I was only twenty-four or five when Geshe Rabten asked me to occasionally teach a group of lay Buddhist followers in Geneva. I was both flattered and terrified. For the first time, I found myself explaining Buddhism in my own words to people from my own culture. This was exhilarating. It awoke my vocation to be a writer.

I was never any good at toeing the party line. As much as I valued the core teachings of the dharma, I was troubled by doctrines that seemed to make little sense either rationally or in terms of empirical evidence. When people asked me questions about rebirth and karma, for instance, I found myself guiltily side-stepping them. I guess I’ve always been a contrarian at heart.

Tibetan Buddhism is built upon a set of non-negotiable metaphysical axioms. If you question core beliefs, like rebirth, then the whole edifice is in danger of collapse. Although I’d been told repeatedly never to accept a doctrine on faith alone, I soon discovered that the phrase zhe sung pa’i chir (“because a scripture says so”) was accepted as “valid proof” to settle thorny issues. That made me squirm. Yet none of my Tibetan teachers—and surprisingly few of my western colleagues — seemed troubled by these mixed messages.

After eight years of being a Tibetan Buddhist, I could take it no more. Neither the doctrinal studies nor Vajrayana practices were working for me. So I travelled to a monastery in South Korea, where I trained in Son (Zen) meditation for four years under the guidance of Kusan Sunim. All I did, three months each summer and three months each winter, was face a wall and ask myself: “What is this?” I abandoned the search for answers and focused instead on the questions.

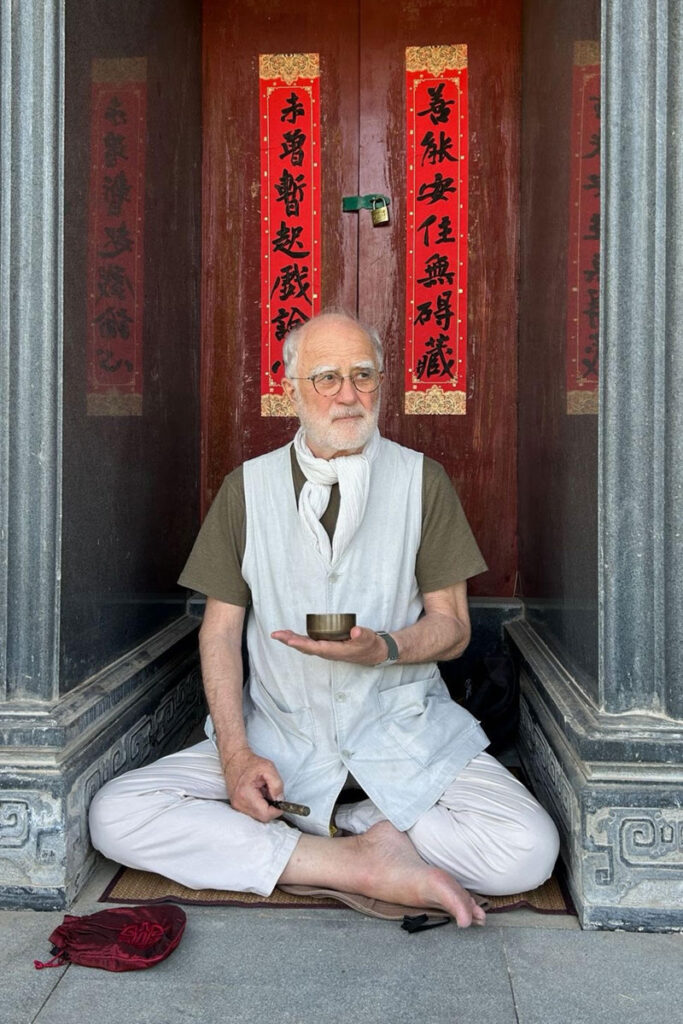

I loved living in Korea. This was the first time I’d been in a country where Buddhism was in evidence everywhere. The dharma, I realised, was not found only in sacred texts and philosophy but was all around me: in the temple architecture, scroll paintings, calligraphy, poetry, even the way people drank tea and admired nature. It was here that I rediscovered my passion for the arts, in particular the practice of photography.

And it’s where I met my wife-to-be, Martine, who was a nun in the same monastery. After Kusan Sunim died, we left together and returned to England, where we joined a small Buddhist community of vipassana practitioners at Sharpham House in Devon. It was there that I began to explore the early Buddhist discourses found in the Pali Canon. I was also invited to lead retreats and give seminars on Buddhism. I worked as a Buddhist chaplain in the local prison as well.

The watershed moment of my career came in 1997 with the publication of Buddhism without Beliefs. It became a bestseller, inspiring many who had the same difficulties with Buddhism as I did, but upsetting all manner of Buddhists who didn’t. It also brought me financial independence for the first time in my adult life, and gave me the confidence to keep pursuing my own path. Three years later, we left the community at Sharpham and moved to south-west France, where we live today.

Buddhism Without Beliefs was followed by Living with the Devil, Confession of a Buddhist Atheist and After Buddhism. My next book Buddha, Socrates and Us: Ethical Living in Uncertain Times will be published by Yale University Press in August, 2025.

[As told to Stephen Schettini, 12/2021, updated 01/2025]

Stephen and Martine Batchelor live in a small village near Bordeaux with their cat Zoë.